I get to moderate a panel of authors at the Bouchercon conference in Nashville this August. We’ll be talking about the childhood books that most affect us as writers today. For me, that’s easy.

I’ve always loved the literary tomboys—-Jo March (Little Women), Scout Finch (To Kill a Mockingbird), Laura Ingalls (Little House on the Prairie), and the Ramona Quimby books. These are ambitious, indelicate girls who aim high, fall regularly, scramble and fight back, often having to earn, not inherit or be given, the love and respect of the characters around them.

I wanted my own protagonist, Jane Benjamin, to be a part of that tradition. But I didn’t want her to experience what so many literary tomboys do. I didn’t want her to be tamed in the final act.

Even before the 1860’s, when Little Women was written, readers have loved and related to young girl characters who cross over into conventionally boyish behavior. Up to a point.

Apparently readers like girls to travel through tomboy terrain, but not to live there forever. Such girls are smiled at by readers through puberty but not after. This may explain why so many literary tomboys get remade. Think of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, of difficult Kate remade into compliant Kate.

When I was a girl, my father, the superintendent of a rural K-12 school district that all fit on one campus, would take me and my brother to school on weekends, presumably to get us out of our mother’s hair. While my father worked in his office on administrative tasks, my brother rode his bike all over, played tetherball, all that. I asked my father to unlock the school library, where I would sit all day and read. My love of reading emerged from that split-pea-colored library, its dusty shelves, its long, empty tables, its hard wooden chairs. Locked in that library, I began with the A’s. Louisa May Alcott. Little Women.

I read that book so many times. I would finish and begin again. I didn’t want a different book to break the spell. For such a self-cloistered kid, I was utterly taken by the rambunctious, adventurous, play-acting, hill-dashing, ice-skating Jo March. But, of course, I probably wouldn’t have liked her so much if she didn’t also always have her nose in a book and ink stains on her fingers.

I’d say I loved everything about it, but that’s not true. I didn’t love everything about it.

Jo spends the whole book claiming she’ll never marry or have children. She wants to be a writer. She chafes at caretaking of any kind.

But then, after Beth dies and Meg and Amy marry off (Amy to Jo’s best friend and spurned suitor Laurie), bereft and jealous Jo meets what I considered to be a very old man, Mr. Baer, and marries him, supposedly because he’s intellectual. She has a passel of kids and runs a family-based school. She becomes a wife, a mom and a teacher and lives happy ever after.

The tomboy has been tamed.

Even as I read and reread this as a girl, I felt mixed reactions. First, I didn’t believe it. I thought Jo would never turn into Mrs. Baer. If she were going to marry, I thought, it would be someone she could alternately boss around and have fun with, like Laurie.

And it pains me now to realize, I think I was a little relieved at her turn. I was worried that Jo’s tomboyishness would render her loveless and alone, a spinster. I bought into Alcott’s soft-focused ending, her tomboy tamed, her gender-role nonconforming girl, re-conformed.

Sadly, I may have been the kind of reader Alcott’s publisher was thinking of, a reader who needed reassurance that a tomboy can recover enough of her conventional femininity in adulthood to win social approval.

This is why I adore filmmaker Greta Gerwig’s 2019 remake of Little Women. She ends with the Baer/March Family pastiche, all gold-hued domesticity, Jo carrying a homemade cake to her parents’ table through a tableau of family activity in a blooming garden, a collaborative, communal school run by Jo and her sisters and their husbands and her parents and their children.

But then the movie repeatedly interrupts that scene with footage implying that golden soft focus is false, invented by the author Jo March, who has actually made a practical, commercial decision to give the readers what they want, a beautiful, tamed, non-tomboy life for her fictional self, even if it isn’t what she wants.

In Gerwig’s film, we, the contemporary audience, are treated to the real happy ending—Jo March watching pages cut, cover folded and glued, her novel being made into a physical book. We see the red leather-bound prize placed in her hand, her name gold-embossed, as independent fulfillment shines on her face, flush as a bride, loyal to her family, but married to her work. A tomboy untamed.

The gap between these two endings—communal and individual—is something my Jane faces over the years of my series. I don’t know where she’ll land, tamed or untamed. Or maybe, like most of us, a little of both, inconclusive. Nonconforming.

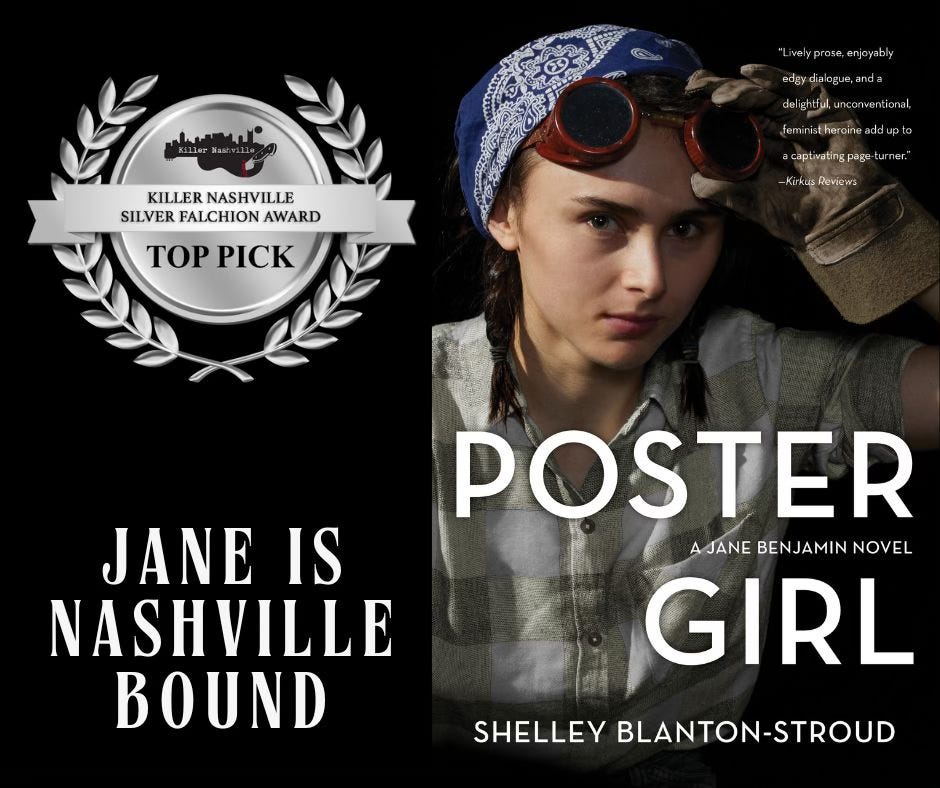

The August conference season is going to be sweet, with both KILLER NASHVILLE and BOUCHERCON taking place within days of each other in the same city.

Even sweeter... Poster Girl's been named a Killer Nashville Top Pick.

Sweetest? All the writers who travel great distances to swap stories, strategies and support. I'm especially thinking of Carmen Amato, whom I loved interviewing for Mystery Review Crew and whose Revenge at the Galliano Club is also a KN top pick.

Learn a little more about Carmen in our conversation.

I hope I see you in Nashville!

— Shelley

So good. I'm place-holding with you another conversation on "tom boy"-ness in my/our lives. Heart!

Love this! I wish I could be at Bouchercon this year, but my hubby and I are leaving September 1 for a three-week safari in Africa. Will miss spending time with you! XOXO